Now Reading: Consequences due to existence of Hereditary Chieftainship in Manipur vis-a-vis ‘The Manipur Hill Areas (Acquisition of Chiefs’ Rights) Act, 1967’

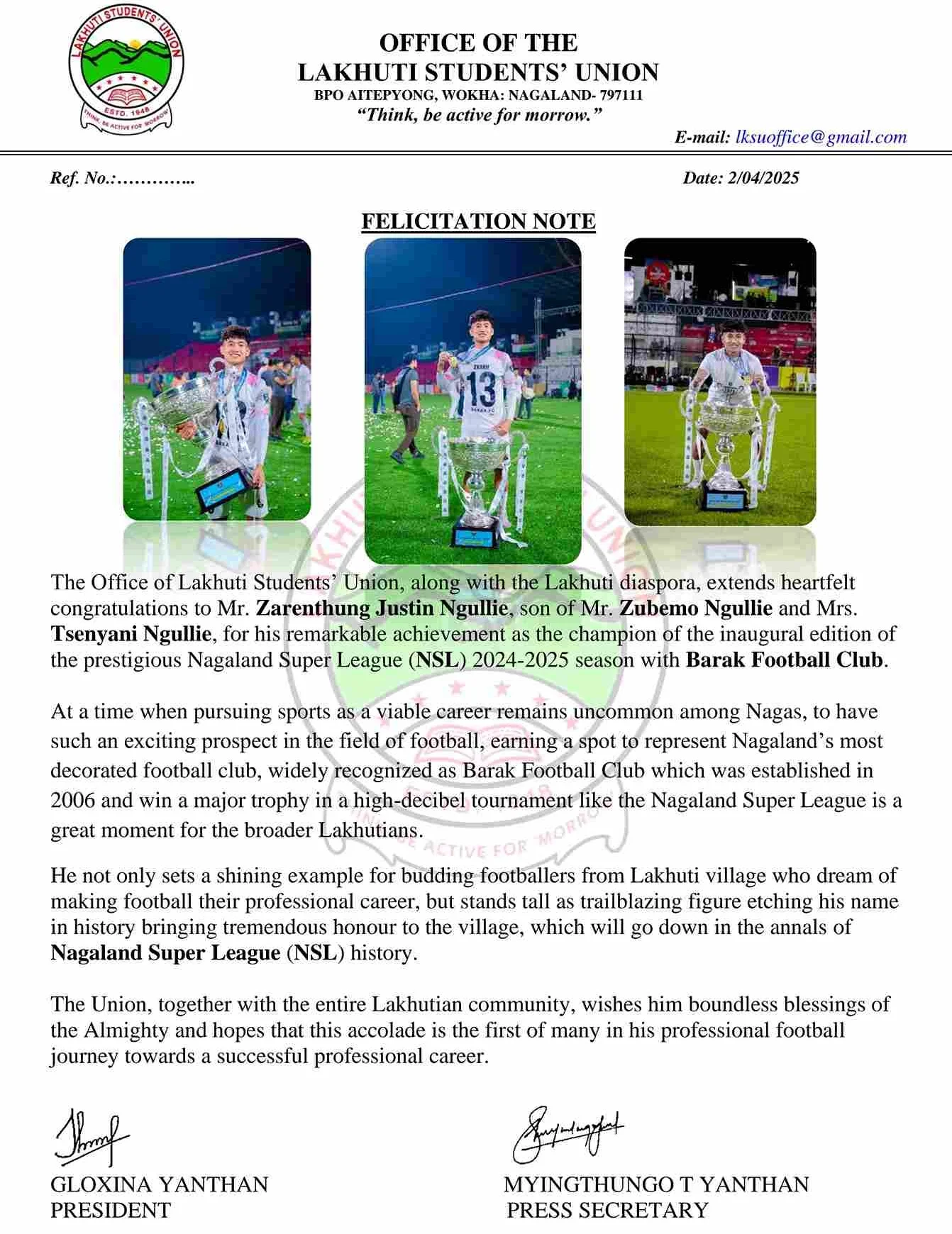

-

01

Consequences due to existence of Hereditary Chieftainship in Manipur vis-a-vis ‘The Manipur Hill Areas (Acquisition of Chiefs’ Rights) Act, 1967’

Consequences due to existence of Hereditary Chieftainship in Manipur vis-a-vis ‘The Manipur Hill Areas (Acquisition of Chiefs’ Rights) Act, 1967’

1. What is Hereditary Chieftainship?

The institution of hereditary chieftainship is well described by W. W. Hunter in his book ‘A Statistical Account of Bengal Volume-VI’ as under:

“The village system among the Kukis is best described as a series of petty states, each under a Dictator or chief (Called Lal), and he can call upon his people to furnish him with everything that he requires. A chief’s son, on attaining manhood, does not general remain with his father, but sets up a separate village of his own. The men of one chief are able to transfer their allegiance to another at will, and it hence happens that a village becomes large or small according as the chief is successful in war or the reverse. The chiefs all come from a certain clan called Aidey, from which all the tribes are said to have originally sprung. Only the son of a chief can set up a village for himself. It is held that all chiefs are blood relatives, and it is consequentially forbidden to kill a chief save in the heat of a battle. The house of a Lal (or chief) is a harbour of refugee. A criminal or fugitive taking shelter there cannot be harmed, but he becomes a slave to the chief under whose protection he has placed himself. Each man is bound to labour three days yearly for his chief, and each house in the village furnishes its share of any expense incurred in feeding or entertaing the Lal’s guests. The chief’s house, also, is built for him by the voluntary labour of his people. The residence of a powerful chief is generally surrounded by the houses of his slaves …” (Hunter, 1876, pp.60).

Also read | Abnormal population growth of Chin-Kuki-Zo in Manipur since 1881

Thomas H. Lewin lucidly provided an exactly similar description of the hereditary chieftainship of Kuki tribes (Lewin, 1869, pp.116-117). Thus, a Chief enjoys enormous power inside the traditional Kuki society. A hereditary Kuki Chief has supreme authority with executive, judicial and military power. Such a Chief claims the absolute ownership of the village under his jurisdiction and the land including forests within the village. He is the commander-in-chief of the village army. In times of war, the chief is supposed to lead the army. The chief is the guardian of law and his words are laws. His power is absolute and his decision in any dispute is final. The chief is assisted by ‘Upas’ who are the elders of the village, appointed by him as advisors. However, he is not bound to abide by the advice of the Upas and has the last word in any matter. The decision of the Upas without consulting the chief cannot be taken as final. ‘Haosa’ is the office of the village chief. It is hereditary, passing from father to son. A daughter has no rights for inheritance. The chief is the Lord of the soil. A chief can allot village land to outsiders, including foreigners, and make them settle in the village as long as they please him.

Villagers have no freedom, and live in the village at the pleasure of the chief. All villagers owe allegiance to the chief with respect and pay such taxes as imposed by the chief. The chief can appoint and dismiss or expel anyone in the village. The villagers do not have the right to oppose their chief individually as well as collectively. However, the power of the chief has its own limitation. For example, if a chief becomes too tyrannical, then the villagers could migrate to other villages deserting the chief. In that case, the chief has no right to stop them as it is a practice sanctioned by the tradition. This serves as some sort of limitation on the power of the chief. But then, it is a very difficult thing for the villagers to do so as even then, the chief has the right to confiscate the movable as well as immovable properties of the villagers who decide to desert him. This means that the villagers have to lose all their properties in case they decide to migrate without the chief’s permission. Thus, it is extremely difficult for the villagers to desert their chief and migrate to another village.

Also read | Facts about Article 371-C: Attempts to tinker with it could trigger a tribal vs non-tribal conflict

2. Communities practicing hereditary chieftainship in Manipur:

According to historical records of authority and the census data of the erstwhile British Government of India, all New Kukis of Manipur, now called ‘Kuki-Chin-Zo’ are immigrants from the Chin Hills of Burma (Myanmar) and the Lushai Hills (Mizoram) who entered Manipur during and after the reign of Maharaja Nara Singh (1844-to 1850). The New Kuki tribes taking settlement in Manipur, are Thadou, Mizo (Lushai), Ralte, Sukte, Mhar, Vaiphei, Paite, Gangte, Simte, Zou etc.

All New Kuki tribes of Manipur have hereditary chieftainship system of village administration which is best described as a series of petty states, each under a dictatorial chief.

The Nagas and Old Kuki tribes (viz. Kom, Chiru, Koireng, Lamgang, Anal, Chothe, Purum, Aimol) also have chieftainship system of village administration but their Chieftainship is not hereditary unlike that of the New Kukis. The Naga Chiefs and the Old Kuki chiefs are elected by the villagers, and they do not claim ownership of the village and forest. Their role is mainly limited to ceremonial and religious activities. They do not have supreme authority and power like the hereditary chieftains. The advice of the village elders and the council binds them.

3. Hereditary Chieftainship exists only in Manipur:

The institution of hereditary chieftainship is anti-ethical to the practice of democracy. There is sufficient room for a Kuki Chief to become tyrannical. The institution of hereditary chieftainship was abolished in the Chin Hills of Burma (Myanmar) in February 1948. In Mizoram, the system of hereditary Chieftainship was abolished by the Assam-Lushai District (Acquisition of Chiefs’ Rights) Act, 1954. In Tripura, the Panchayat System has replaced the institution of Kuki Chieftainship, which functions under the Tripura Tribal Areas Autonomous District Council.

“The Manipur Hill Areas (Acquisition of Chiefs’ Rights) Act, 1967” was enacted to abolish the institution of hereditary Chieftainship with all its rights and privileges. The Bill of the said Act was passed by the Legislative Assembly of Manipur on 10th January 1967 and received the assent of the President of India on 14th June 1967. Subsequently, the Legislative Assemble notified the said Act on 20th June 1967, under the official notification No. 3/32/66-Act/L. However, the said Act though enacted in 1967 has not been enforced yet due to objections from the frantic lobby of the politically powerful Kuki Chiefs. The institution of hereditary chieftainship still survives and is currently in practice among the New Kukis inhabited in Manipur due to non-enforcement of the said Act. Presently, Manipur is the only State in the Northeast where the hereditary Chieftainship exists.

4. Abnormal increase of Kuki villages in Manipur:

The basic reason for the abnormal increase of Kuki villages in Manipur is due to failure of the Government of Manipur to enforce the “The Manipur Hill Areas (Acquisition of Chiefs’ Rights) Act, 1967”. But surprisingly, the said Act was referred to the Hon’ble High Court of Manipur for settlement of a dispute regarding the chieftainship of a village in Churachandpur in 2016 [H. Mangchinkhup vs. State of Manipur in Writ Petition (C) No. 605 of 2016]. According to land ownership systems prevalent in the Kuki society, only one son can inherit the chiefship of a village from his father. Other sons of the chief often venture out to set up their own villages. ‘The Manipur (Village Authorities in Hill Areas) Act, 1956’ requires a minimum of 20 houses to establish a village. However, defying this provision of the Act, many Kuki chiefs are still well known in establishing villages with a few houses, enabling them to make most of their sons as village chiefs. Illegal Kuki-Chin migrants from Myanmar and Bangladesh provide an opportunity to all the ambitious sons of a Chief to fulfil their aspiration of becoming village chiefs. This practice leads to rapid growth of new villages with assimilation of Kuki refugees/illegal migrants as members of the the villages. Table 1 shown below depicts the pattern of district-wise growth of villages in Manipur during the period 1969-2023:

Opinion | I am a Meitei Manipuri, and here are my thoughts on the present Manipur

Table 1: District-wise growth of villages in Manipur during 1969-2023:-

The abnormal growth of villages in four districts viz., Churachandpur, Kangpokpi, Tengnoupal and Chandel is discernible from the figures shown in Table 1 above. The abnormal growth of villages implicitly and explicitly tells that a huge number of Kuki refugees/illegal migrants had entered Manipur in the last few decades. This inference is commensurate with the pattern of abnormal decadal population growth of the Nomadic Chin-Kuki-Zo as shown below in Table 2:

Opinion | Where is Manipur headed?

Table 2: Pattern of population growth of Chin-Kuki-Zo in Manipur during 1881-2011:-

5. Growth of Kuki militant groups in Manipur:

The existence of the hereditary chieftainship has attributed to rapid increase in the number of Kuki militant groups operating in Manipur. The reason for this phenomenon is that the chief of every Kuki village may set up a militant group, being the commander of his village army. Only the Kuki chiefs have the monopoly of military, executive, legislative and judiciary power. Therefore, the Kuki chiefs often acted aggressively with impunity towards other ethnic groups living in Manipur in the past. There were Naga-Kuki clash in 1992-94 and Paite-Kuki clash in 1997-09 before the current crisis with the Meetei/Meitei community. According to an unconfirmed source, there are at present 45 Kuki militant groups in Manipur includsive of 25 groups who signed the Suspension of Operations (SoO) Agreement. Notably, the SoO Agreement was signed between the Government of India, the Government of Manipur and two Kuki militant umbrella groups namely, Kuki National Organization (KNO) and United People’s Front (UPF) on August 22, 2008 and it has been continuously extended till February 29, 2024. The existing SoO Agreement needs to be revoked for the following reasons among others:

- The SoO Agreement has created a conducive environment to strengthen the militant outfits and they are responsible for bringing in the Kuki migrants, providing them with language / combat training in their camps and also using the illegal migrants as a labour force for poppy cultivation, arms running, drug trafficking etc.

- The acceptance of illegal migrants as soldiers for Kukiland has led to the phenomenon of expanding Kuki militants’ population who are accommodated in available lands such as the Reserve and Protected Forests, protected sites and wildlife sanctuaries giving adequate room for raising encroachment, deforestation and other illegal activities.

- The SoO Agreement paves the opportunistic way to raise funds from narco-related activities, such as poppy cultivation, opium production, drug trafficking etc. As such, the current violence in Manipur is a fall-out of terrorism orchestrated by Kuki militant groups funded by narco money, mediated allegedly by Kuki policy makers and high-ranking officials using Kuki illegal migrants from Myanmar as soldiers in addition to the Kuki militants who are under the SoO Agreement.

5. Necessity for abolition of hereditary Kuki chieftainship:

The existing institutions of hereditary Kuki chieftainship in Manipur are outdated forms of dictatorial authority that affront the basic principles of Indian democracy. By strictly enforcing ‘The Manipur Hill Areas (Acquisition of Chiefs’ Rights) Act, 1967’, the growth in numbers of both Kuki villages and Kuki militant groups in Manipur can be checked. The villagers in Kuki villages do not enjoy the rights of freedom as provided in the Constitution of India. While the Kuki chiefs and their children have progressed immensely, most of the common Kuki people remain below the poverty line and are highly vulnerable to exploitation by the Kuki chiefs. It is high time even if belated to abolish the institution of hereditary Kuki chieftainship for ensuring peaceful coexistence among all ethnic groups in Manipur. Once the said Act is enforced in letter and spirit, the same will be a guiding force towards bringing peace and normalcy in Manipur. With the implementation of ‘The Manipur Hill Areas (Acquisition of Chiefs’ Rights) Act, 1967’ in letter and spirit, the existing traditional system of chieftainship will get automatically abolished with compensation to the affected chiefs. ‘The Manipur Land Revenue and Land Reform Act, 1960’ will get simultaneously extended to the hill areas thereby authorizing the State Government to acquire the rights, title, and land in the hill areas. The said Act may be regarded as one of the first steps towards democratization of hill administration in Manipur. By placing certain restrictions on the powers of the chief and introducing adult franchise at the lowest level of administration as well, the Panchayat Raj institution may be introduced to democratize the Kuki society so that the common villagers can become aware of democratic values and practices of the Indian democratic system.

The authors can be reached at yugindro361@gmail.com.

This is not a Ukhrul Times publication. UT is not responsible for, nor does it necessarily endorse its content. Any reports or views expressed are solely those of the author or publisher and do not necessarily reflect those of Ukhrul Times.

References:

- Lewin, Thomas H., The Hill Tracts of Chittagong and the Dwellers Therein with Comparative Vocabularies of the Hill Dialects, Calcutta: Bengal Printing Company Ltd. (1869).

- Hunter, W.W., A Statistical Account of Bengal, London: Trubner & Co. (1876).

- Shakespear, J., The Lushei Kuki Clans, London: McMillan and Co. Ltd. (1912).

- Gangte, T.S., The Kukis of Manipur: A Historical Analysis, New Delhi: Gyan Publishing House (2003).

- Hutchinson, R.H. Sneyed, The Chittagong Hill Tracts, Kolkata: Kreativmind (2002).

- Changsan, L. & Borgohain, Alpana, The Traditional Institutions of the Kukis Living in the Dima Hasao District of Assam, International Journal of Research in Social Science, Vol. 8, Issue 4 (April, 2018).

- Haokip, George T., The Institution of Chieftainship in Kuki Society, E-Pao (April 29, 2009).

- Singh, L. B., Hereditary Kuki Chieftainship should be abolished, The Sangai Express (November 29, 2023).

- Singh, L. B., Hereditary Chieftainship exists only in Manipur in the Northeast, E-Pao (December 01, 2023).

- K. Yugindro Singh, M. Manihar Singh & Sh. Janaki Sharma, Abnormal population growth of Chin-Kuki-Zo in Manipur since 1881, The Sangai Express (February 13, 2024).

Ruivah

Dear Yugindro Singh and etal

I am writing to you regarding your recent article titled “Consequences due to existence of Hereditary Chieftainship in Manipur vis-a-vis ‘The Manipur Hill Areas (Acquisition of Chiefs’ Rights) Act, 1967” published in By Ukhrul Times, February 25, 2024 – 9:39pm, https://ukhrultimes.com.

I found your analysis of the consequences of hereditary chieftainship among Kuki tribes in Manipur insightful and thought-provoking. It is true that Kuki populations explosions have been greatly attributed to Kuki Hereditary system.

However, I noticed that while you extensively discussed the ills of hereditary chieftainship, there was a notable absence of discussion on another significant issue affecting tribal communities in Manipur: the Manipur Hills Village Authority Act 1956 (MHVA).

As you are aware, this act contains provisions that perpetuate undemocratic power structures, particularly through the automatic appointment of the hereditary headman as the ex-officio chairman of the village authority under section 4 clause IV of MHVA 1956.

I believe that addressing the provisions of the MHVA in your next writing would provide a comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by tribal communities in Manipur.

*Both the hereditary chieftainship among the Kuki tribes and the permanent chairmanship of the headman aming the Naga or other tribes under the MHVA are undemocratic and unethical practices that warrant critical examination and discussion. Notable these unethical provisions are now existing only in the Manipur state*

Therefore, I kindly request you to consider exploring the implications of the MHVA in your future writings. Provisions that were relevant in those times may not be so today after half a century time lapse.

Analyzing the effects of this legislation on tribal governance, community participation, and democratic principles would contribute significantly to the discourse on tribal rights and governance in Manipur.

I look forward to reading your future writings on this important subject.

Sincerely,

Y Ruivah

Heisenberg

As we go through the article it is obvious that this is a meetei agenda, even before you know the author’s name it is obvious. The statistics maybe true, also there definitely something here to think about. But it’s a shame that the author conflated those with the meetei’s narrative of narco terrorism and the need for land reform. Too obvious.